Alan Henriksen: Contrapuntal Vision

Balance is the keyword of Alan Henriksen’s intimate and elegant imagery, from his black-and-white landscapes of Hawaii, Maine, California and New York to his recent color photographs of an antique dealer’s establishment in Bar Harbor. Henriksen takes pains to ensure that no single element dominates the frame, and that each piece of the composition carries equal weight. It’s an interesting approach, one that’s well suited to his exploration of natural terrain where growth often coexists with decay. Born in 1949 in Richmond Hill, Queens, New York, Henriksen began taking photographs at the age of nine, and has found frequent exhibition outlets for work that combines acute visual clarity with a highly personal emotional impressionism.  Alan Henriksen

Alan Henriksen

Tell me a little bit about your background.

I am employed as a software engineer. From 1974 through 1983 I worked as a sensitometrist and software engineer at Agfa-Gevaert’s photo paper manufacturing plant in Shoreham, Long Island—which was formerly Nicola Tesla’s laboratory. One of the papers we coated was a contact-printing paper called Contactone. This was a paper once used by Cole Weston to print his father’s negatives. One perk I enjoyed was that I was permitted to take outdated paper from the lab, enabling me to spend countless hours printing my 8 x 10 negatives without having to be concerned about the cost of the photo paper.

When did you start taking photographs, and what provoked your interest in the medium?

Although I began photographing in 1958 and making prints on print-out paper in 1959, photography was just one of my many hobbies until 1964, when I discovered the photography of Edward Weston, Ansel Adams and Paul Strand during a visit to my local library. My response to the Weston photos in Peter Pollack’s The Picture History of Photography was so overwhelming that I knew at that moment that photography would become my lifelong passion. In retrospect, I feel that my previous experience with print-out paper prepared me to appreciate the beauty I saw in those photos.

What other influences helped direct the course of your work?

Early on I read every photography book and magazine I could get my hands on. During that period, the greatest influence on the development of my seeing and on my ideas about photography was Edward Weston, which he communicated through both his photography and his writing. One line from his Daybooks—“Whenever I can feel a Bach fugue in my work I know I have arrived”—led to my interest in the music of J.S. Bach, and I would often listen to recordings of Bach’s music while looking through books of Weston’s photographs. Weston and Bach have been, in a sense, lifelong companions, and I hold each of them in the highest esteem. One side note: To my mind many of Weston’s finest works don’t seem fugal at all, but instead have the transcendent sweetness of a Bach aria. Rock, Point Lobos, 1998

Rock, Point Lobos, 1998

I took great interest in the work of many other photographers, including Brett Weston, Paul Strand, Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, Paul Caponigro and Ansel Adams. I was honored to know Adams not only through his photography, but also as a friend and mentor. In 1967 I did a very brash thing by mailing him some of my photos and asking for advice about pursuing a career in fine art photography. He replied with a two-page, single-spaced, typewritten letter expressing his opinion that it was unwise for anyone interested in photography as an art to pursue a career in photography merely to earn a living. After praising my “seeing,” he said he would like to follow the progress of my work and invited me to send him more prints whenever I felt I had made some progress. He concluded by saying, “You have something to say, and world needs all it can get of creative beauty.” I continued my correspondence, as well as occasional phone conversations, with Adams until 1970, when I attended his Yosemite Workshop. I kept in touch afterward, and from late 1977 through mid-1978 got to work with him and with Paul Caponigro on David Vestal’s project for Popular Photography magazine concerning the declining quality of photo paper at that time. During this period I also became acquainted with a truly great photographer, William Clift, with whom I have since had countless engaging conversations on photography.

How would you characterize your own work in terms of music? I feel that it has a chamber music quality.

The music of Bach is what I’m really closest to. I think my work could be called contrapuntal. I don’t have a single element that stands out as being “the” subject. In contrapuntal music, every part is important. That’s what I like to do in my photographs. I don’t make images of an isolated subject with a background supporting it. Leaves and Rusty Can, Super's Junkin' Company

Leaves and Rusty Can, Super's Junkin' Company

Bar Harbor, Maine, 2008

When did you start shooting color?

My color work began in fits and starts in 2005, after I acquired my first digital SLR. Then in 2008, right before I left for a trip to the Maine coast, Bill Clift and I were discussing his color work, and he asked whether I had been doing anything in color now that I owned a digital camera. That was enough to put the wheels in motion, and I decided soon afterwards to visit Super’s Junkin’ Company in Bar Harbor, a place I had driven past but never visited, and to work in color as well as black and white.

Not that it’s all that important, but do you work with film or digital? Or both?

I work in both film and digital, although most of my recent photographs (including this series) have been made with a digital SLR. In the past I’ve worked with 8x10 and 4x5 view cameras, as well as a medium-format SLR. I plan to use the view cameras again in the not too distant future.

What was your thinking in terms of shooting this series in both color and black and white?

I enjoyed the challenge of deciding on the spot whether to organize each composition in terms of luminance or color. Of course, since I was photographing with a digital camera, I was free to change my mind afterward, during the editing phase. Ansel Adams was fond of saying that the photographer should visualize compositions in chords of tones. I have found that this notion, extended to color photography, is perhaps even more closely aligned with the idea of a musical chord. Chords of colors can create feelings equivalent to the experience of consonance or dissonance in music. And, as we all know, colors can clash, which can be a good thing. I’ll never stop working in black and white, but color opens up whole new dimensions. The kinds of moods you can get in color are impossible in black and white. And vice-versa. Leaves and Trash, Super's Junkin' Company

Leaves and Trash, Super's Junkin' Company

Bar Harbor, Maine, 2008

I love the color palette. It’s full of strange tonalities that evoke both growth and decay. Is this intentional? And are these found colors, or do you tweak them slightly in Photoshop?

To answer your second question first, many of the colors in these photos were altered while editing in Photoshop. My goal is always to produce a photograph that is true to what I feel about life as a whole. When working in black and white the photographer manipulates gray values and contrast, globally and locally, to achieve the ultimate expressive print. By extension, when working in color the photographer can also manipulate hue and saturation. I like to paraphrase a line from Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style: A change to a photograph, however slight, produces a corresponding change in meaning, however slight.

Although I wasn’t literally thinking in terms of growth and decay, those terms do approximate part of what I was feeling when I made these photos. I accept without sentimentality the idea that ordered systems, such as living things and manufactured objects, are a temporary bulwark against entropy.

The images are very tactile; you can almost feel the dankness in images like “Leaves and Trash” and “Leaves and Rusty Can.” I don’t think black and white would impart the same effect.

The tactile quality of my photographs no doubt stems from my early experience working with large-format cameras. The rendition of texture and substance is still central to my visual “language,” even when working with a digital SLR. When I chose the images to include in this series, it was important to me that the color relationships were vital to the overall feeling I was trying to communicate.  Kelp Seawall, Maine, 2006

Kelp Seawall, Maine, 2006

You seem drawn to subject matter that’s in a state of decay. Even your black-and-white landscape images are often evocative of a sense of things breaking down, whether organic or inorganic in nature. Why does this type of subject matter resonate so strongly for you?

It may be coincidental, but just days before I began photographing this series, I finished reading Alan Weisman’s excellent book, The World Without Us, which speculates upon what might happen to various manmade systems were mankind to suddenly vanish. Although I was not consciously reflecting upon the book while photographing, newly processed ideas sometimes have a way of insinuating their way into my compositions.

Put another way, you make decay very seductive from a visual perspective. Any comment?

I’ve been photographing along the Maine coast for over 40 years, principally in Acadia National Park and its environs, a region whose natural scene is at once idyllic and harsh. In any given patch of forest one will typically see young saplings and healthy trees intermingled with storm-toppled trees, some still leaning, others lying on the forest floor in various states of decay. And the coast is lined with storm- and surf-battered rocks, whose forms and textures speak of their primal past. So it’s a good place to contemplate the cyclical nature of both living and non-living things. In my photography I am devoted to trying to communicate my sense of the world, colored, no doubt, by my idiosyncratic history of photographic encounters. Pond Foam, Somesville, Maine, 2007

Pond Foam, Somesville, Maine, 2007

The natural environment seems to be your primary focus. When you do photograph a location that bears the imprint of people, it’s an antique shop full of castoff, obsolete items. And it’s interesting that you photograph it in such a way as to show nature gradually reclaiming this space. Is there an implicit commentary implied here?

If there is, it’s purely subconscious. I don’t actually think that way at all. In fact, if you were to tap into my brain while I’m photographing, you’d find it pretty boring. I’m not thinking philosophically while I’m photographing. An important point that Bill Clift has driven home over the years is that when you photograph you really need to be completely innocent. That’s something I believe. Words tend to get in the way. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t these other influences. Any number of photographers shooting the same scene will come back with different images, completely different perspectives on life. I believe that keeping the verbiage out gives all of my unconscious equal access, equal opportunity for expression. I find beauty first of all in the combination of textures and forms and lines. I try to think in terms of the overall experience of the photograph, and to get as much of who I am into the image. Having said that, I think there’s a mixture of hope and dread regarding the future of mankind. I think that’s worked its way in there.

You pack a lot of visual information into each frame, but somehow avoid making things feel claustrophobic. Are you conscious of these kinds of pictorial dynamics when you’re composing an image?

It is important to me that every compositional element contributes something to the overall statement. An artist in any other medium, whether it be painting, sculpture, music or dance, would never permit extraneous, distracting elements to remain in a composition, and I feel the same way about my photography. Aside from that concern, I admit that I greatly enjoy the challenge of working with complex, visually dense subjects, puzzling out what I hope are meaningful compositional solutions along the way. I realize that in so doing I am walking a knife’s edge, the other side of which lies the dreaded specter of multiplicity. Weeds and Junk, Super's Junkin' Company

Weeds and Junk, Super's Junkin' Company

Bar Harbor, Maine, 2008

Certain of the Super’s Junkin’ images—through a symbiosis of color, framing and perspective—are suggestive of hidden depths, spatially and metaphorically. It’s as if there are stranger and perhaps more abstract dimensions lurking just beneath the surface.

Thank you very much for that observation, and you are absolutely correct. For starters, the photographer can play with appearance of space and scale (which, after all, is always an illusion) by the degree to which context is either included or excluded. Ansel Adams was a master of creating a sense of physical dimensionality, which he called presence. But these aspects of apparent space are, for me, subordinate to the overarching goal of consciousness-raising. I like to say that as photographers we are limited to the two spatial dimensions of the print, but there is no limit to the number of dimensions of experience.

When you say consciousness-raising, are you referring to yours, the viewer’s, or both?

I think in some ways the goal of the artist is similar to that of a scientist; the artists that are preserved throughout history are the ones that actually added something—a new concept, a new of looking, a new perspective. They weren’t simply rehashing what came before them. Even in traditional photography, I think there will be new things happening several hundred years from now, if people are still photographing. Even though they will be going to the very same places that we go today, the same subject matter, and so on.

Is this an ongoing series?

Yes. In fact, in 2009 I returned to Super’s Junkin’ Company and other nearby antique shops, and made additional photographs for this series.

How do your see your work developing in the future?

I hope to continue photographing the landscape, naturalistic details, and modern-day cultural artifacts of the Maine coast and Long Island. Once I retire from my current career as a software engineer, I expect that I will begin to seek out other venues and projects. Ice and Puddle, Nissequogue, NY, 1976

Ice and Puddle, Nissequogue, NY, 1976

(Pay a visit to Alan Henriksen’s fine website to see more of his work: www.alanhenriksen.com. I profiled him in issue #8 of COLOR magazine.)

Gordon Parks: A Voice in the Mirror

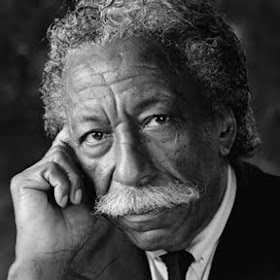

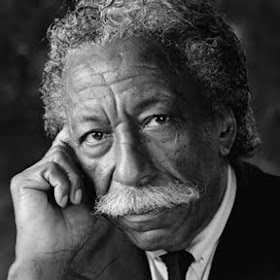

“I have never gloried at being the first black photographer to enter those closed doors at Life magazine, Vogue or any of the other places. I like to feel they were opened for my race as well as me. I did realize that I making fresh tracks, but I never carried the responsibility around on my back like a sack of stones. I simply did my best without asking favors because I was black. Time and time again those tracks have been filled, and this is reason to rejoice.” Gordon Parks (Photo by Steven A. Heller)

Gordon Parks (Photo by Steven A. Heller)

These words were written by Gordon Parks (1912–2006) in the third of his four autobiographies, Voices in the Mirror, published in 1990. The convictions they embody were manifest in every facet of a remarkable life in which Parks made big tracks in numerous creative arenas. He was the first African-American to join the staffs of Life and Vogue magazines, and the first to direct a major Hollywood film. But breaking racial barriers was only part of his story. As a child growing up in rural Kansas, he suffered extreme poverty and racism without succumbing to bitterness or prejudice. On his own at 15, he played piano in a Minnesota brothel, cleaned up in a Chicago flophouse, worked as a railway porter and played semi-pro baseball. He discovered photography at 25, and demonstrated a quick and lasting affinity with the medium. Sensitive photos of Chicago’s rugged South Side earned him the first Julius Rosenwald Fellowship and work as a Farm Security Administration photographer alongside Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans. Parks went to work for Life in 1949, and for the next two decades produced eloquent and hard-hitting photo essays on poverty, racial segregation, and civil rights leaders Malcolm X and Martin Luther King. He also excelled at sports, fashion and portrait photography. His restless creative spirit eventually led him to Hollywood, where he made history with the groundbreaking films The Learning Tree (1969), Shaft (1971) and Leadbelly (1976). When I interviewed Parks in 1991 for Camera & Darkroom magazine, he had just finished Voices in the Mirror and was working on a new novel and screenplay, finishing a book of poetry, planning another photo book, giving lectures, and spreading good vibes wherever he went. Although our conversation took place almost two decades ago, Parks' plea for tolerance and understanding between people of all ages, races and walks of life remains as relevant as ever.  Red Jackson, Harlem Gang Leader

Red Jackson, Harlem Gang Leader

You’re busier than most men half your age. How do you manage to keep so many irons in the fire?

I’m using energy left over from my youth [laughs]. The projects give you energy. I get it from my work, from my typewriter when I sit down to work on my novel or screenplay or poetry. Actually, I don’t feel too well when I’m not working, maybe due to a fear of depression from inactivity. It’s actually easier for me now to keep up the pace. When I experiment, I do so with more confidence, and I work with more confidence.

Why did you decide to write another autobiography, and are you satisfied that this is the definitive version?

I don’t suppose anything’s ever done to your complete satisfaction, but it’s getting fabulous reviews all over the country, so I suppose it’s satisfying to some. I wrote it because people I met through my lectures felt there were a lot of unanswered questions about my successes and failures, things not addressed in my previous books, so I decided to write another.

What’s the most important message in Voices in the Mirror?

One must take a look in the mirror at himself, at those around him and at his past and see what they meant to him. In this particular book, the message that comes through to me is that people from all walks of life, all colors and races and religions, helped me get to wherever I got to, and that I must always look at what they are, not the color of their skin.

You’ve had significant success in not just one, but several artistic mediums. Do you feel there are still worlds for you to conquer?

Well, I don’t feel like I’ve done anything. I think of myself as just working very hard to survive, and that’s what it’s all about. I never thought about being a success. I always thought of survival. If survival turned into success, well, all the better. What I strive to do is come as close to perfection as I possibly can in whatever I do. I want to compose music better, I want to photograph better, I want to write better, make better poetry, paint better—do all those things better. American Gothic

American Gothic

What are some of the projects you’re currently working on?

Right now I’m busy composing a lot of music as well as writing a screenplay and novel about the English painter J.M.W. Turner. After I finish the screenplay, I hope to be able to film it in England. But first I want to finish the novel, which I’ve been working on for about four years. It’s very difficult, because here I am, a Kansas kid from the prairies trying to put myself into the world of a young English painter in London in the 18th century! I’ve also got a book of new poems coming out that will deal in part with the recent Middle East war, and there are plans for a new photo book.

What type of photographic subjects interest you today?

I only do very special things. I don’t photograph that much unless something really excites me. I’ve been doing some experimental color work with fruits and vegetables, and was recently commissioned to photograph the prairies of Kansas. But it’s very difficult for me now to find inspirational photo essays for magazines the way they exist today. They don’t have the same depth that they had when I worked for Life magazine. I think it must be very difficult now for young photographers starting out, since they don’t have the spiritual or financial backing that we had in the old days.

What do you think of Life magazine today?

Well, it’s good for what it is, and it has some exciting color and unusual photographs, but what I’m saying is that when Henry Luce [Life’s original publisher] was alive, the photographer was sent out on a story and allowed to work on that story until he was finished, no matter if it took ten days, ten weeks or a year, because Luce believed in photography, and in giving the photographer what he needed to get a good story. If you needed an airplane, you got an airplane. If you needed a ship, you got a ship. With that kind of backing, you were not rushed and were able to give your subject matter full respect.

For instance, when I approached a sensitive story like Flavio or the Fontenelle family [two of Parks' photo essays on poverty in Brazil and New York, respectively], I didn’t even take my camera out for a week, because I wanted the people to get to know me and gain some respect and knowledge of what I was trying to do. And after doing a story on a poverty-stricken family, I could never just forget them after the story was published. I always felt like a part of that family and somehow or other kept in contact with them long after the assignment. Flavio Da Silva

Flavio Da Silva

You have been one of the few photographers to actually make a difference in your subjects’ lives. For instance, your 1961 story on the Brazilian boy Flavio and his family, who lived in a notorious Rio de Janeiro slum, generated a tremendous response in letters and money from Life’s readers. Do you feel the same depth of response is possible today considering how images people are continually exposed?

I doubt it. With the Flavio story almost $30,000 came in one week from the magazine’s readers and thousands of letters asking about him. I doubt seriously that you can get that kind of response today. There seems to be a blanket of callousness over the universe. You see a lot of news on TV, day and day out, with images of children starving and being abused in different parts of the world, so people become sort of calloused, and would probably not react as fully as they did back in those years. Yet I still feel photography can be a useful tool for change. I think it can help and can point up issues and things that will make people question what’s going on.

Which of your colleagues at Life made the biggest impression on you?

I was good friends with and admired Carl Mydans, Alfred Eisenstadt, Eugene Smith and David Douglas Duncan, among others. I also knew Robert Capa very well. He was very talented and courageous. I remember when I was a young man working as a porter on a train Capa was traveling on. When he got off the train, I handed him his bag and told him I would be out to join him at Life one day. He gave me a silver dollar and said, “Okay, I’ll leave a locker for you.” Years later Robert and I were frolicking half-drunk down the Champs-Élysées in Paris, and I turned to him and said, “Thanks for saving me that locker.” He replied, “What locker? What the hell are you talking about? You mean that was you?” Mother and Child, Harlem

Mother and Child, Harlem

What are the most important qualifications a young photojournalist needs today?

First, you have to believe in yourself. And you have to find stories in which you can assert yourself and say something about the world around you. If you don’t have anything to say, your photographs are not going to say much. You should also read a lot, be able to do research, and study all art forms—not just photography—so you become thoroughly aware of what exists around you. Otherwise you’re just out there aimlessly shooting pictures. You also have to create situations for yourself. Look around and generate ideas. Sometimes magazine editors don’t tell you what to do, but sit back and wait for you to bring them ideas.

When you worked for Life, how much control did the editors exercise over your work?

There was always a control; there had to be some sort. We would send our stuff in from Europe or wherever we were traveling, the lab would make the contact prints, the editors would select the best pictures and hand them over to a layout man who understood the story. You could insist upon certain shots; sometimes you won, sometimes you lost. But overall, I was very pleased about the way Life handled me and my photographs. They did not shuttle me off onto just black stories, and I didn’t go anywhere as a black reporter or writer. I went as a reporter from Life magazine, period. That attitude was very helpful to the magazine and myself.

You often landed tough, gritty assignments. Did you seek out these types of stories?

Well, I suggested some of them, and the editors suggested some, perhaps because of the success I’d had with my story on gangs in Harlem and the crime stories I’d done. Since I was a person who had suffered many of the same things I encountered on those stories, the editors felt I would be more adept at getting good coverage. I had been trained in the worlds of poverty and crime and so forth. I understood it because I’d been through it and knew where to look for it.  Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali

Did you attempt to imbue such stories with a political subtext?

Not really. I always thought in terms of humanity. If my work had a political aspect, it came from others’ reactions to it. All I tried to do was to open people’s eyes to the worlds of the underprivileged. I worked out of my concern for individuals. When you’re doing the work, you are thinking of the individual, not the political impact that work may subsequently have.

You wrote articles for Life as well as took photographs. Was your writing edited much?

Oh, yes. Sometimes for the good, sometimes not. I had to watch it, especially when I was covering the black militants back in the 1960s: people like Malcolm X, Eldridge Cleaver and Bobby Seale. When I first started doing those stories, Life was not sure that I would be as objective as they would like, because I was black and I had a common interest with the black revolution. And I’m sure that the black militants, realizing that I worked for a big, conservative white magazine, were not sure that I would report in their favor. So I had to keep a close eye on the editors so they wouldn’t change things or use a word I didn’t want to use. In the end, both sides greeted me with understanding.

You spent a lot of time with and became close to Malcolm X and Eldridge Cleaver. Did their philosophies influence your thinking in any way?

I went in with my own attitude. I’d seen enough and heard enough to know that I had to follow my own course, not theirs. Eldridge Cleaver asked me to be the Panthers’ official public relations person when I was with him in Algiers, but I refused. One of the Panthers asked me if I would still write A Choice of Weapons the same as I had written it years before. When I said yes, he replied, “You mean you feel the same, even with all these white honkies following us around here with machine guns?” [The Panthers were under police observation at the time.] I said to him, “You have a 45mm automatic pistol on your lap, and I have a 35mm camera on my lap, and my weapon is just as powerful as yours.” Malcolm X

Malcolm X

Assess the degree of progress in social gains since the civil rights protests of the 1960s.

You can’t deny that there’s been a lot of progress. Blacks and other minorities are in very responsible positions. There are a lot of young people being educated now and going on to achieve positions in politics and the corporate world that wouldn’t have been able to do so back then. Yet there’s still a great underclass developing. With all the progress, it still isn’t enough. It’s not swift enough.

Do you see any present-day Martin Luther Kings or Malcolm Xs?

I don’t know. I’ve noticed certain young leaders and I hail them when they do something particularly good. However, most of our strongest leaders have been destroyed. King, Malcolm, Medger Evers—all shot away, assassinated. There are some young people who seem to be on the move, and I think they will emerge as responsible leaders. We have more black mayors and politicians and so forth, and that’s encouraging, but I don’t see anyone rocking across the horizon. Some of them are trying, but they don’t seem to have the magic to stir the populace the way King or Malcolm did.

Do you still feel yourself to be part of the civil rights struggle, as well as effective voice for change?

I’ll always be a part of the struggle. How effective I’ve been and will be, history will say that. I will not attempt to say something like that. I like to think of myself as part of the struggle for all humanity. I think in terms of universality. And I think if I have achieved certain things a lot of people haven’t, it’s because I think that way. I’d like for a woman in Russia to understand my poems and photos and paintings as well as a woman in Harlem. I’ve been successful to the extent that I have not allowed the anger and the hatred that I could have had for certain people bottle me up and let me go to bed with stress every night. Instead, I used that anger in a forceful, creative way, rather than in a self-destructive way. Ingrid Bergman, Stromboli

Ingrid Bergman, Stromboli

Where does society look for answers to the some of the evils that afflict it?

I’m afraid racism is always going to be with us. Unfortunately, we can’t rid ourselves of it. Poverty is always going to be around. Violence will always be here in some form or another. I think the answers lie with younger people and with education. Yet, you have to be optimistic about the future. There’s no sense in going on if you think that everything is going downhill, if you have no reason to connect with the world around you.

What would you most like to be remembered for?

I don’t particularly care about being remembered, but I do want my work to live on. I’d like my work to be remembered for its universality. I’ve written an Irish novel called Shannon, and am now writing this novel on Turner, and I’d like to make films of both. It’s best not to get stuck in that black world. Duke Ellington, one of my favorite composers and a good friend, advised me to listen to Ravel and Debussy and Beethoven and so on, because they would help me to broaden my musical horizons. And so I don’t just write black poetry or paint black pictures. I think blacks should find out as much as they can about their history and where they came from and so on, but not allow themselves to shoved into a corner just to do black things. If you put yourself in a corner, it’s nobody’s fault but your own.  Children with Doll

Children with Doll

“I trust time. It has been my friend for a long while, and we have been through a lot together. Now I ask only that it lend enough of itself to say a proper goodbye; to thank it for giving me faith when others chose to doubt me; for refusing to let me hate those who chose to hate me. It taught me that triumph or failure can be hypocritical, and that both should be looked at with beseeching eyes.” — Voices in the Mirror

(All photographs by Gordon Parks. To learn more about this great American and artist, please visit http://gordonparkscenter.org, and http://www.gordonparksfoundation.org.)

Barry Underwood: Metamorphoses

Photographer Barry Underwood engineers audacious transformations of wilderness landscapes by synthesizing elements of film, theater and land art into unexpectedly moving hybrids. Having scouted suitable terrain, he creates light installations that often exist apart from their visual documentation. While the works blur the line between installation art and photography, the unifying factor is light: dancing elegant arabesques in dark woodlands, emerging mysteriously from watery depths, or darting around trees like some alien vessel in a science fiction film. Ultimately, Underwood’s light takes on a life of its own as it shapes fleeting meta-narratives of energy, beauty and transfiguration. Barry Underwood (with Sophie)

Barry Underwood (with Sophie)

What influences shaped your thinking about photography?

The first photographer to make me think about constructing images instead of taking images was Robert Frank. There’s a piece he made for his daughter Andrea that’s a kind of combination of painting and photography; it showed me that you could apply an image into a photograph as opposed to just taking it. I also like the way that Francesca Woodman works with environments, and how she works with the idea of photography, even through something as simple as positive-negative processes.

What was thinking behind this body of work?

I was a theater major, and used to build sets, so I think much of the theatricality of the work comes from that. The early images in this series essentially channel set design: the natural objects function as set dressing, the sky as a cyclorama, and the lights as the performers, if you will. I had been looking at my photography and noticing lights in the background that were perhaps incidental, just part of the atmospheric or visual background. From there I started thinking in terms of how to incorporate that light as the main subject matter.

So you’re treating these natural locations like stage settings.

That was the original idea. Over the years I started thinking more about land art and installation art, and about how these objects interact in the landscape.

Orange, 2007

Orange, 2007

Environmental issues are implicit in this work as well.

They are actually now pushed more to the forefront. I was dong a residency in 2009 at the Headlands Center for the Arts outside San Francisco, which included a discussion on eco-visual criticism, and so I’ve started thinking more about environmental issues. Wondering about the kind of damage that photography is doing, the damage that even I as an artist am responsible for, and how can I help change things. I’m trying to say in a subtle way how these natural settings can be altered with these installations. Putting a blue line across several redwood trees, (in the image Blue Line), instead of being a magical thing that’s happening in the environment, became something that points more towards an issue that could be a problem.

Can you clarify how you see photography damaging the environment?

Chemicals for one. E-waste for another. Like, where do the sensors come from? Where do the computer chips come from? Silicon Valley is toxic because of leakage from underground tanks. Photographers think: Well, we’re not pouring chemicals down the drain as much anymore, which is good. But electronic manufacturing and electronic waste is a very bad thing, and might actually have a greater impact than traditional chemistry, and on a bigger scale. What does it mean to be an environmentalist as a photographer? It’s almost in contradiction. So I think about the footprint that we leave, and in that sense the images might be a little persuasive or subversive in order to get people thinking in a different way about these things. It’s literally like putting a spotlight on something.  Blue Line, 2010

Blue Line, 2010

Do you think this theme comes out in the images?

That’s kind of where I’m headed now. Some of these images are a couple or five years old, so I’ve been slowly going from these ideas about theater to ideas about one’s photographic footprint. I’m trying to make these images function in the way that photography functions in a vernacular sense. Being referential in some way, or documenting an event subjectively. I think about all that and try to make these images very subjective, kind of hyper-real, or surreal, or a kind of heightened activity or performance. That’s kind of how cinema plays into it a bit. It’s an exaggeration, a stylized way of looking at something. Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie in Mr. and Mrs. Smith, that’s definitely an extreme to the everyday.

How does the light play into the notion of the footprint we leave behind?

The work that I was making wasn’t so much about that. The light was more about how photography functions, about the kind of vernacular that photography has around it. It was just being a little more heightened. Looking at the environment around me from a photographic perspective, and doing these kinds of installations, helps me relate to the planet, as in, how can I interact in this landscape? So the landscape becomes more than just a field or hill or mountain.

Can we get into a bit about what goes into these images, how you make them?

I’m working with film, because these images require long exposures, anywhere between 15 minutes and four hours. With the light being applied to the film over a period of time, what starts out as a simple small line becomes broader as the light bleeds onto the emulsion in that area. I’m kind of playing with the process of photography as much as the vernacular of photography.  Blue Ice, 2004

Blue Ice, 2004

What do you use to create the light patterns?

I use a variety of party objects: balloons, LED lights, glow sticks. I try to keep them as battery-operated as possible, so I can recycle the batteries, and I can re-use the LED lights themselves. Using LEDs allows me to try things again, whereas with glow sticks or anything chemical-based I have a shorter window in which I’m able to photograph these things.

Not all these images are done outdoors. Blue Ice, for example...

That’s a diorama.

You built that.

Yeah, I totally built that one.

That one looks totally artificial compared to the others.

A few of the pieces are dioramas, although I haven’t finalized any in the past couple years. They wind up being almost like maquettes at this point, which is kind of where they were originally. I would have certain ideas and that needed to be interpreted on a grander scale. For this image I had an idea for a piece of ice just kind of pushing through one tree and into another one. I used that idea as a maquette, and I liked it a lot, so I kept it as a final piece. I see them almost as drawings. That’s where everything really starts, with a drawing. Every piece has a drawing companion to it.  Trace (Yellow), 2009

Trace (Yellow), 2009

Even when working with actual landscapes, you’re altering them, so they are congruent visually with the artificiality of the dioramas. Any differences in how you work with each?

I’m more anal-retentive with the dioramas. I scrutinize every detail. The ones I do on location I have to be very open to problematic issues about availability of light, and of whatever might come my way, either an animal or a person.

For images like Pink and Trace (Yellow), are you creating the light during the exposure, moving it around, painting with light, so to speak?

No, those are actually static pieces, in which you can walk around. Pink is probably ten or 12 feet high. Trace (Yellow) is about 350-feet long. For these kinds of things I build a suspension system in the trees; I’ll climb one tree, tie a rope, then climb another tree and wrap it around or tie it to that tree. And from that rope I could drop down, I use this stuff called spider wire, so you can’t see it. These are actually suspended lights. You’re right, there is a little bit of movement in Trace (Yellow), but it’s there to raise a question about the provenance of this light.

I realize that you probably don’t like to focus too much on how these are done.

Right. It’s more about calling into question photographic realities. The way we understand things in terms of photographs. That’s where I’m being referential. I’m pointing back to the process of photography and pointing back to the language that’s used and the theories that are around photography to conceive these pieces. Like the pumpkins can be pointing back to other photographers, like the Joel Sternfeld pumpkin piece, right? Some of the work points back to land artists and painters as well. I think about contemporary abstract painting. I think about historical landscape painting, especially the Americans from the Hudson River school. We have these kind of grand skies and magnificent illuminated landscapes. And the two of them coming together in some sort of crash. Pink, 2008

Pink, 2008

What factors into your choice of locations?

Availability. In recent years I’ve been making work in residencies. In 2008, I was at a place called I-Park, in East Haddam, Connecticut. That’s where I made Trace (Yellow), Blue, Pink and a few other pieces. What was nice about that place was that I could build things, and I could come back to a particular location day after day, and take up to a week to create something. Trace Yellow took four days to build. When I was at the Banff Center in Banff, Alberta, it was more of an in-and-out approach. I was limited to temporary structures that could only be up for one evening, which means I had to be more creative.

I need to find places where I’m able to have time to myself to think about the environment around me, and to have time to construct these things. Wintertime is when I have these things scanned, and then clean them up in Photoshop. As far as how I handle Photoshop, I think in terms of traditional photography. For most of the older pieces, say, until 2007, everything was done in the darkroom. I wasn’t even scanning these except as reference images. So with Photoshop I work in terms of dodging and burning, adjusting color, and spotting. I try and keep it as minimal as possible. But I have been thinking about continuing the construction: starting with the construction on the film, i.e., the application of light, and then constructing a little bit further in Photoshop. Not too much, but just a little subtle addition or shifting of something. Miwok Trail, 2010

Miwok Trail, 2010

Besides availability, what else do you look for?

Wildlife is always a concern. Not doing any damage to them, first of all, and not letting them do any damage to me. Weather conditions are a major factor, so I’m always paying attention to what the weather’s going to be like, and hoping that I can get the right conditions. Moisture is a big problem. This past summer the Headlands had a lot of moisture because it’s right there on the Pacific. I pay attention to the lunar chart to make sure that the moon is out if I need it to be out, or not out. I try to align myself with any ambient light popping off of the city. San Francisco is great in this respect because of the fog, and the way that ambient light bounces off the clouds and the fog. I only have so many hours to work with, so I can’t set these things up a day ahead of time. I might only have a couple of hours before sunset, so it’s a mad dash to get the installation up, get everything focused, and get the camera shutter opened in time. Once I begin the exposure, this weird kind of tranquility sets in.

In terms of aesthetics, do you look for certain types of locations from a visual perspective?

Yeah. I think working at the Headlands Center was the trickiest, because there were a lot of buildings there and I had to make sure they weren’t going to be in the shot. Like I said, I usually start from a drawing, but that’s just to get a thought moving around about a piece. I’ll do a lot of walking around the environment, or I’ll just sit in the space. I’ll do test shots with a digital camera and try to figure out how I want to compose the shot. Then I’ll maybe go back and do another drawing or draw on the computer how I want to line things up.  Headlands, 2009

Headlands, 2009

So when you’re looking at a new space, it’s almost like collaboration between you and the landscape.

It is. The pieces also draw from the energy of the people who assist me. It’s not really there in the read of the work, but it’s definitely there for myself. Sometimes a composition might shift a little bit depending on who is helping me. Some people have made suggestions that I’ve incorporated. For example, the staggering of lights might be a little dependent on who puts them there.

Once you’ve taken the image, what do these installations look like? Would they resemble the photographs if you hadn’t taken the photographs? Do they have a life of their own apart from their photographic representation?

When I talk about documentation, it’s in the context of how installations are sustained and understood through photographs, like Richard Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. I think about the way land artists, like Andy Goldsworthy for example, document their work. Some of his work actually functions through the lens, so that’s how I kind of think about my installations functioning, through the lens. But some of them do have a bit of a life of their own as installations. The people who assist me can come and view them. I’m on residencies with other artists, so they can also come and see them, depending on their size. Trace (Yellow) was something that we could all walk around and walk through while it was being exposed, because the exposures were so long that the film didn’t pick us up. Norquay (Yellow) was another installation that people could access and view. And I sometimes send out announcements, so other people can experience them.  Norquay (Yellow), 2007

Norquay (Yellow), 2007

Sometimes the pieces work solely on the photographic plane. Sometimes they will be successful as a photograph, and sometimes they won’t be successful as a photograph, but they’ll be successful as an installation. That’s something I’ve been trying to figure out how to do on a more permanent sense. It doesn’t have to a permanent piece, but something that’s up in a location for a while. I’ve been thinking about how to shift gears a little bit more towards that. Especially here in Cleveland Heights, where I live. I’d like to do a piece in the neighborhood.

I imagine these pieces exert a kind of trance-like or meditative effect on viewers.

I wish I understood that a little bit more. I can never get into somebody else’s mind. I usually get responses like: This looks beautiful, or How did you do it? But I do sense that people consciously try to figure out what the images are saying, which is nice.

The otherworldly forms and colors evoke a kind of alien presence, especially images like Blue and Aurora.

Yeah, I like sci-fi too. My mom calls them that. She calls them my alien shots. It’s a heavy influence. There’s some Close Encounters of the Third Kind inspiration there. It’s like when the little star kind of moves across the sky. It’s very subtle. There’s also the Dr. Who-inspired, something that’s bigger on the inside that it is on the outside kind of thing.

Blue, 2006

Blue, 2006

You’re an Assistant Professor and Head of the Department of Film, Video and Photographic Arts at the Cleveland Institute of Art. Does your work there influence or impact your personal work in any way? And vice-versa?

One of the beautiful things about working in an academic setting is working with brilliant colleagues and sharing ideas back and forth. The students are always hungry for knowledge, and they also come up interesting ideas and concepts, so it’s a very reciprocal and rewarding environment.

(Further exploration may be undertaken at www.barryunderwood.com. This interview was conducted in late 2009 for a Color magazine article.)

Veneta Zaharieva: Urban Instability

Cultural and personal dislocation are at the heart of Veneta Zaharieva’s photography, which frequently makes use of layering—visual and otherwise—to transcend objective representations of the urban environment. She offers up her thematic conceptions and obsessions through a complex visual code designed to unsettle rather than reassure. This is particularly noticeable in her “City Fairytales” series, a kaleidoscopic conjunction of commercial and residential buildings seemingly on the point of collapse, the result perhaps of unseen fault lines destabilizing the urban terrain. A licensed attorney as well as a photographer, Zaharieva knows the importance of communicating complex visions with clarity of expression, while ensuring that the end result resists easy interpretations.  Veneta Zaharieva

Veneta Zaharieva

Where were you born?

I was born in Sofia, Bulgaria, in a quiet neighborhood (or at least it used to be that way, during my childhood). My mother had me at the age of 40, despite the risk that she might lose her life or me during birth. I have a sister who is 14 years older than me, so that made me the “istursak,” which means “unexpected baby” in Bulgarian. I grew up mostly with my father; my mother had to work from early morning until late evening. My father was very sensitive man with plenty of old-fashioned manners. There was a very old woman in the building we lived in. She was the wife of a famous Bulgarian painter, so every time we met her on the stairs my father saluted her by lifting up his hat and calling her family name. I remember that pretty well because I never saw anybody else doing that. Looking back, I realize that my father lived in a time he didn’t belong to—he had an aristocratic childhood, but lived as a working class fellow after the socialist revolution. That drastic change made him extremely sensitive, with nothing but beautiful memories about the times he used to be happy and carefree, along with my grandmother, grandfather and uncle. City Fairytales, 2005

City Fairytales, 2005

Did you develop a visual sensibility at a young age?

I spent some time writing about my father because of this question. Being mainly with during my years of growth, I realized how painful life was for him, how much he missed the “old times,” and how disappointed he was with his everyday reality. I have my father’s sensibility; I know what pain is by looking at the faces of people. My intuition never lies, and I gradually developed the ability to see beyond surface appearances. There were times when I was frequently left alone for long periods of time without toys to play with. I developed an ability to see in ordinary things imaginary toys and to play with them in a self-created reality, invisible to all but me.

Did your environment help steer you towards a creative path?

I’m not sure, because I grew up with the dream that I would one day become a lawyer, as my grandfather was. I never had the chance to meet my grandfather; I knew his face only from family pictures, but I know he was a great man and I wanted to be just like him. Looking back at that time, I cannot see anything that stimulated or suggested “artistic development,” even on a primitive level. After my first year at school (at the age of eight), my parents signed me up on a competitive swimming team. My life became very predictable: classes, swimming practice, homework. Only the weekends were different. I’ve never been good in drawing or singing, but I was good at writing, an ability that appeared after high school. I improved my writing skills during law school at Sofia University.  City Fairytales, 2005

City Fairytales, 2005

When did you begin taking photographs?

Fairly late, compared with most photographers. After graduating from law school in Bulgaria, I applied to the University of San Francisco, School of Law, to continue my education. Before my acceptance, I moved to the United States to see what it was like to live there. I was 24, and that’s when I had my first camera. I knew nothing about how to use it, so I took some photography classes at the City College of San Francisco. I became hooked on the medium, and spent two semesters studying photography.

What formal training have you had?

After my graduation from USF, I returned to Bulgaria and practiced law for about two years. But during that time I never stopped taking pictures. I also read photography magazines and attended every photo exhibition in Sofia. I wanted to learn more, so I applied to the Academy of Art University in San Francisco, and was accepted in Illustrative/Fine Art Photography.

Have you been influenced by any other photographers? Some of your “City Fairytales” images evoke certain Harry Callahan composites.

Everything influences us or evokes certain thoughts or dreams. I respect artists who go beyond the mainstream and conceptualize their visions through unusual moods and tones. I’m amazed by the Pictorialists. I find the work of the Dadaist artists striking even today.

During my time at the Academy of Art University I discovered the images of Alfred Stiegltz, Josef Koudelka, Alexander Rodchenko and Harry Callahan. More recently I have been inspired by Michael Kenna, Simon Marsden, Misha Gordin and Stanka Tsonkova-USHA. City Fairytales, 2005

City Fairytales, 2005

What’s the photographic scene like in Bulgaria?

Unfortunately, we do not have a photographic tradition comparable to the Czech Republic or Poland. Photography was always subordinate to other forms of art (like music and sculpture) during the Communist era. Today, there are many digital artists who share their work on the Internet, but most of the critiques come from people who don’t have a clue what photography is all about.

What gave rise to the “City Fairytales” series, and what led you to the layering effect?

I used to frequently encounter statements along the lines of: “Photography is merely about the reproduction of reality,” and “There is no creativity to photography because the camera does all the work.” I have always found such attitudes to be narrow and reductive. The “City Fairytales” series is my reaction to such statements, and with these images I have tried to create alternative realities. My intention is to “sound” their echoes beyond the obvious, and to encourage viewers to see and think beyond the image itself. Even more, I want them to be able to feel the image, even if they do not understand it. I try to evoke controversial emotions and imaginary in each viewer’s mind because I believe in the subconscious world and the power that resides within it. The layering technique is done in camera, and is utilized to achieve a more complex and ambiguous vision. It is also proof that photography need not be limited to simply pressing the shutter and capturing “reality,” but that it can also be about imagination and pre-visualization.

In other words, you find straight images confining?

I believe that the straight images can be expressive if the photographer has the vision and the ability to make a unique statement. City Fairytales, 2005

City Fairytales, 2005

So you find a greater “truth” in a non-representational approach to the urban landscape?

I cannot say definitively, but in general, yes.

What themes or ideas are you trying to communicate with this work?

Most of the houses you see in this series are already gone. Developers indifferent to their beauty destroyed them in order to build modern, sterile buildings. My reaction to this process was to visually preserve as many as possible while conveying their story, so that people might discover what they blindly passed by every day.

Do you work with silver-gelatin, digital, or both?

I work with silver-gelatin, cyanotype, salt process, gum dichromate or digital, depending on the message I want to convey. The “City Fairytale” series is full of symbols, signs and perspectives, so I find it expressive enough to print it with digital inkjet. Alternatively, there are series that I find it necessary to print with a cyanotype emulsion. In general, the final presentation is part of the process, and it depends on what I aim for in terms of statement and vision.

What symbolic representation is the layering meant to convey?

It allows me to present in visual terms a different kind of reality, not one you can necessarily see or touch. I view reality in line with Einstein’s general theory of relativity—that is, not in an absolute, literal way. Just because one cannot see something doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. The layering also symbolizes how a particular issue or problem might be best addressed through multiple perspectives. City Fairytales, 2005

City Fairytales, 2005

In addition to imbuing the images with a lot of visual energy, this layering projects a sense of instability, both literal and metaphorical.

I totally agree. Although truthfully, I do not care what the reaction is as long as there is a reaction of some sort. Basically, the interpretation is left to the mood and intelligence of the viewer.

The visual distortion also conjures a Gothic atmosphere, casting the city as a kind of foreboding, unstable environment. Is this your perception of the urban landscape?

Yes, it’s fair to say that an “unstable environment” is implied in my images. We are generally comfortable with the urban places we grew up in; however, we sometimes also fear them due to the unpredictable ways in which they change. For example, I grew up in a neighborhood of Sofia where many creative people lived—artists, journalists, university professors and the like. After democratization, wealthy people from small towns began buying property there, and that old neighborhood spirit went away. The new arrivals seem to care only about money, and don’t realize the potential for community. There is no “hello” when you meet someone on the stairs, no smiles. In this regard, time moves fast and brings many, often unwelcome, changes.

This is a depopulated vision of the city. Why have you excluded people from it?

I find the depopulated approach as an unexpected solution to an understanding of the urban environment. For me, people are the ones who suggest what the time frame is. I see the time frame as the key ingredient to this series: The lack of it pushes you into asking questions, into exploring your feelings and imagination. City Fairytales, 2005

City Fairytales, 2005

This approach contributes to a certain dreamlike atmosphere.

Absolutely. However, I believe in the subconscious world and the great power that resides in it. In my images I constantly provoke the conscious part of the mind, so that the subconscious one arises and expresses itself. I think people who look carefully at my work are capable of their own interpretation, which I find exciting. I would rather provoke unexpected interpretations than underestimate the viewer’s intellect by presenting only a single, unalterable point of view.

(I profiled Zaharieva in the April 2008 issue of Black & White magazine. Visit her work at: http://www.venetazaharieva.com.)